The 1st Erhu Rhapsody was composed by Wang Jian Min (王建民) in 1988, which falls under the third phase (1976 – 1989) of the developmental phase in contemporary erhu music, marking the end of the Cultural Revolution. While keeping to the traditions brought forward by his predecessors, Wang Jian Min was also absorbed in introducing, exploring and creating new and unique forms of expressions, playing a pivotal role in the development of contemporary erhu music. In his compositions, he strives towards “雅俗共赏,中西并存” as his compositional philosophy (i.e. they must satisfy what he perceived should be the basis of music – “listenable” and aurally acceptable by the masses, while combining refined artistry drawn from both the Chinese and Western musical concepts in terms of structure, form and language (王建民,2003). By combining Chinese and Western musical elements, he refers to compositions exploring and combining traditional elements from China’s folk music, set against modern and contemporary compositional techniques of the Western musical concepts. Although he pioneered many new trends and is constantly experimenting with new ways of composing so as to break away from the traditional musical style, he firmly held that “创新度”是“新而不怪”(i.e. the degree of innovative ideas in music should not be too profound or avant garde that it becomes difficult for general listeners to appreciate) (王建民,2003).

“Erhu Rhapsody No. 1” is Wang Jian Min’s first major erhu composition. Using this piece as a basis for study, I would like to trace how Wang expanded upon forms and concepts from the Western musical tradition, which allowed him to break free from the traditional style of Chinese music writing, producing a work which is highly coherent yet contrasting in content, novel in style, yet not losing its sense of aesthetic beauty. By exploring the scales and harmonic colours, musical structure, thematic materials, textures and virtuosic elements, which are not usual characteristics of traditional Chinese music, we could gain an insight to how Western concepts and techniques of writing were imbued and built upon. Furthermore, I would also take a look at how folk and traditional Chinese music elements were preserved and developed in the piece, which affected the choice of scale (which essential was drawn from the West), rhythms and pulse used, as well as breakthroughs in erhu performing techniques.

Main Points

Phase 1 (1949 – 1966)

Phase 2 (1966 – 1976)

Phase 3 (1976 – 1989)

Ø Scale used

According to 孙凰 (2004), 陈静(2008), this piece is written using a self – constructed 9 tone scale C D Eb E F# G Ab Bb B. This scale corresponds to the third mode in Olivier Messiaen’s limited transpositional scale/ mode, where Messiaen was fascinated by scales that only had a few transpositions. It consists of three segments, each comprising of a tone followed by two semitones.

Tracing the general trend of the use of this scale throughout the piece, we could observe how he made use of this scale at different transpositions and may perhaps provide us some insights into the structure of the piece.

We could categorize the piece into six sections. The introduction uses T2, followed by a section which generally revolves around T1 before moving to T2 to lead in to the next section. The fourth section is classified by instability, employing the scale at different transpositions but T0 seemed to be the central mode here. This is followed by a section of more stability in T0. In the final section, the music leads back to T2, which is the mode in which the piece began.

Ø Motivic Idea

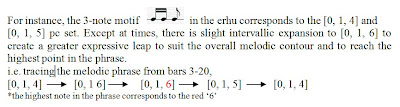

4-17 is a prominent idea, especially seen in how the introduction is stemmed from it, as well as in the opening phrases of motivic ideas ‘a’ and ‘d’ (as well as the variants of ‘d’). This served as a unifying feature in the piece across sections and in a sense also blurs distinction between motifs ‘a’ and ‘d’, which are found across sections. It also undergoes intervallic expansion and expanded to form a larger set as seen in Andante.

This motivic idea is inherent in the mode employed by the composer.

4-17 is implicitly a symmetrical set, however this symmetry does not seem to be utilized on the musical surface.

Even when 4-17 is not utilized in other motifs, the composer sometimes made use of other sets which bears resemblance to 4-17 in terms of IcV. (absense of maj 2nds and tritones)

IcV of 4-17: <1,0,2,2,1,0>,

E.g. piano transition (bars 59-60), the two alternate chords are based on 5-21.

IcV: <2,>

Adagio section (at bar 62), the melody was built upon 4-20.

IcV: <1,>

One of the earliest Chinese piece that uses non-programmatic/ descriptive title, resembling Western Classical tradition.

Instead of writing in the usual ternary form with a balanced nature (flanked by an introduction and a coda that is free in tempo) characteristic of traditional Chinese pieces, ‘rhapsody’ is employed as a structural vehicle. This is something that is absorbed from the Western musical concept.

Due to the highly integrated structure in terms of fluidity in motivic ideas (distinct yet similar) and scales used, lack of clear cadential point, as well as ambiguity in tonal center makes clear distinction of form difficult, especially in the traditional sense. The sense of tonality or key centers are largely established by ostinato pedal pattern, or motivic gestures emphasizing a particular note more often than the others.

However, we could possibly say that this piece resembles a ternary form to a certain extent, although it does not adhere strictly to the usual prescriptive characteristics of ternary form.

Introduced the idea of 4-17 (prominently utilized throughout the piece)

Tonally rather stable, in the key of D major

Main transposition of scale: T2

Section A (bars 2-73)

Motif ‘a’ (bars 3 – 7) and ‘a1’ (bar 26 – 27). Based on 4-17.

Tonal center: A (maj/min)

Motif ‘b’ (bars 62 – 63). Triad as prominent feature (vertically and horizontally) – contrast with ‘a’.

Impression of tonal center: (C maj à) D major

Main transposition of scale: T1

Transition? (bars 84-99)

Motif ‘c’.

Tonal center: F major à Bb major

Main transposition of scale: T2 (same as intro)

Section B (bars 100-237)

Motif ‘d’ and subsequent variations. Based on 4-17 again (coherence - mirrors that in section A?).

Motif ‘e’

Contrast from previous sections:

Tonal instability: G (maj/min) --> Ab major --> D minor --> D major --> G major

Pass through many transpositional scales (see scales point above).

Higher energy level compared to section A

Similarities to Section A: themes somewhat ‘broughtback’

e.g. Motif reminiscent to motif a (in octave equivalence)

Erhu Cadenza – reminiscent of motif a1 and b1

Ways in which it differs:

T0 instead of T1

C major instead of home key of D, although the erhu cadenza ended off in D

Mood

Coda (bars 267 - )

Motivic ideas ‘a’ and ‘d’ from sections A and B are brought back. Emphasis of 4-17, which is explored further.

Tonal center: Return to D major

Transposition of scale: return to T2

Ø Influences from the Chinese Folk elements

Juxtaposition of major and minor 3rd in 4-17 – characteristic in 苗族飞歌

Pulse and the frequent change in time signature – characteristic in 彝族阿细跳月

Using wooden part of bow to hit soundboard – imitate bamboo dancing of 苗族

Hit against the snake skin with the right hand and the pluck the strings with the left hand – imitate hitting of drums

Conclusion

(still under construction...)