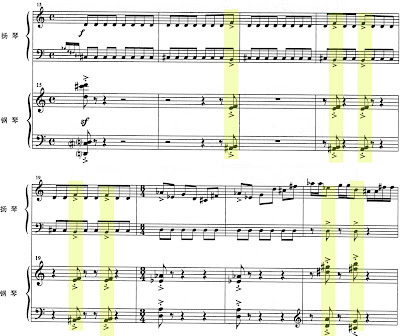

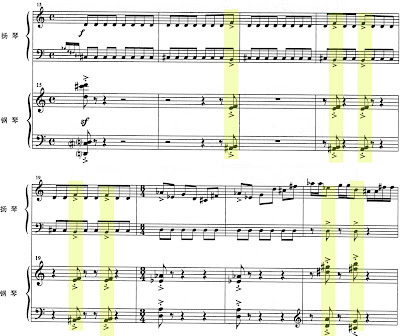

I felt it was fascinating how the composer managed to infuse so much rhythmic interest into what looks to be very regular rhythms on the surface (e.g. semiquavers, quavers, crotchets, and sometimes long held notes). Perhaps it was the way he combines these rhythms with staggered entrances, coupled with the persistent use of accents on weak and off beats (syncopations) that upsets the regularity of the pulse, injecting in the music a sense of rhythmic interest. But because there are many little recurring fragments of melodic ideas subjected to syncopated treatment throughout, that gave it the feel of regularity within irregularity and vice versa. I feel that this unique mood portrayed can be relieving in some extent.

Of course, the use of syncopations in Chinese music is not uncommon, especially for accompaniment but it is actually quite rare to actually find such extensive use of syncopations for the melody. Instances can be heard at 0’20 – 0’30; 0’43 – 0’51 etc. (see diagrams for illustrations)

Of course, the use of syncopations in Chinese music is not uncommon, especially for accompaniment but it is actually quite rare to actually find such extensive use of syncopations for the melody. Instances can be heard at 0’20 – 0’30; 0’43 – 0’51 etc. (see diagrams for illustrations)

Another very prominent aspect is the frequent change in time signature.

Right from the beginning (0’00 – 0’15), the subtle change in time signature from 6/8 passing through 2/4 before going to 3/4 made the transition in meter smooth. (i.e. 6/8 and 2/4 both can be sub-classified into 2 groups, except that 6/8 consists of groups of 3 quavers while 2/4 consists of groups of 2 quavers. Leading in to 3/4 from here would not upset the metrical feel too much).

Right from the beginning (0’00 – 0’15), the subtle change in time signature from 6/8 passing through 2/4 before going to 3/4 made the transition in meter smooth. (i.e. 6/8 and 2/4 both can be sub-classified into 2 groups, except that 6/8 consists of groups of 3 quavers while 2/4 consists of groups of 2 quavers. Leading in to 3/4 from here would not upset the metrical feel too much).

It was also interesting how he creates a little tension in the piano part before ushering in the yangqin (main character, if speaking from the operatic point of view) by inserting an extra crotchet beat to build up a little climax. Note the change from 4/4 to 5/4 in that little 2 bar link from 0’15 – 0’20. Once the yangqin enters, the meter went back to 4/4 again.

During the last time where this 2 bar link is featured, the composer surprises us with a 4/4 to 3/4 change instead of a 5/4 change which we have been conditioned to expect, from the many previous appearances. (heard from 13’07 – 13’10)

Sometimes, even though the time signature remains unchanged, the displacement of regular metrical pulse is actually created by the playing of registers, for instance at 0’51 – 0’59, 4’20 – 4’36.

The registral change also aids in creating the impression of rhythmic complexity as heard from 13’53 – 14’19, where the texture slowly climaxes towards the end of the piece.

I also found instances where the perceived meter is not what was stated in the score, due to the rate of harmonic change and phrase structure that conflicts with the actual time signature. One example would be the middle section, 6’02 – 6’54 or a more decorated version from 7’48 – 8’40.

I also found instances where the perceived meter is not what was stated in the score, due to the rate of harmonic change and phrase structure that conflicts with the actual time signature. One example would be the middle section, 6’02 – 6’54 or a more decorated version from 7’48 – 8’40.

The main accompanimental figuration was also ingeniously ‘tampered’ with so that its recurrence is not always exactly the same. Although it was only altered from 6/8 to 5/8, but I feel that such little variation actually added variety to the already interesting music. (Compare between 0’59 – 1’05 and 1’28 – 1’33)

There is an instance at 11’45 – 11’54 where the feeling of antecedent and consequent phrase (period) relation could be subtly felt. This is brought about by the addition of just one quaver note which allows the consequent phrase to have the last note rooted in the dominant or tonic, giving it a slight sense of closure. Or maybe it’s also due to the more even time signature of 10/8 in the consequent phrase as compared to 9/8 of the antecedent phrase.